TEST LONGREAD

slide_author

In the run-up to the coup, multiple factors can be distinguished to explain the emerging fragility and the clash in 2012.

After the ’91 military coup led by General Amadou Toumani, a strong military was perceived as highly unwanted. Democratic elections were held after a national conference and in the years after, more power was given to civilians, particularly by the in 2002 elected President Amadou Toumani Touré (commonly referred to as ATT).[1] The northern part of Mali benefitted more autonomy over state rule, while the power of the army was weaker in the north. At the same time, most donor efforts developed in the south of the country, where cotton production flourished. Distribution to the north was limited as a consequence of limited infrastructure[f1]. Patterns of poverty have been much more severe in the north, which resulted in a feeling of underrepresentation and marginalization in the eyes of the northern population towards the government in government seat Bamako and towards the international community. Blind to the emerging unrest, Mali’s ruling elite was unable to control rebellion in the north in 2012. In and around Bamako crowds attacked the homes and businesses of Tuareg and other light-skinned Africans, especially targeting the property of suspected National Movement of the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) sympathizers.[2] President Touré was quickly accused of failing to arm and equip his soldiers, for siding with the rebels and high-ranking members his government were accused of collusion with narco-traffickers. After an ongoing unsuccessful battle, due to a lack of supplies, the underfed and underpaid soldiers staged the coup d’état.

The military coup motivated international action. While violent threats and rebellion accumulated in the region, the conflict gets a central place in the political debate and the media. Mainly, economic sanctions and military support offered immediate relief.

This is the version from http://ldrumm.webfactional.com (see next slide for other version)

Against this backdrop, how can we place the patterns of the run-up to the conflict in a regional context? Is restoring peace in Mali enough to address these root causes and create long-term stability while surrounding countries show similar patterns, which influence the conflict locally? How should social, economic and political development goals and security goals be integrated for long-term solutions? And how should the analysis take into consideration the changing dynamics of the conflict? This living analysis [LINK ABOUT THIS DOSSIER ARTICLE] aims to answer these questions by analyzing the conflict in Mali in 1) a comprehensive way and 2) to generate together with [NUMBER] experts frequent updates on the changing analysis according to changing patterns and additional knowledge.

This map shows the activity of non-state armed groups per region in Mali during the years 2012 -2015. Regions are coloured according to three types of groups (Islamist extremists, independence fighters, autonomy fighters), based on the ACLED Dataset. Click on the buttons in the right-hand corner to view different years. Click on a region to view more information on the type of activity reported there. For more information on the various non-state armed groups active in Mali, please click here.

The underlying causes of the conflict in Mali are to a large extent socio-economic causes. The Sahel is one of the most difficult places on earth to survive. The majority of the Malian population lives in poverty, economic opportunities are limited, infant mortality and illiteracy rates are high, life expectancy is around 50 years. Particularly the northern part of the country is subjected to severe droughts and food and water scarcity. During such crises, immediate humanitarian assistance is crucial to provide relief and protect the population against vulnerabilities.[1] Such short-term solution needs to be followed by strengthening institutions and economic structures that enable opportunities suited to the population’s subsistence.

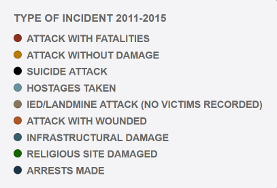

This map shows the location and type of conflict-related incidents in Mali from 2011 – 2015. Click on an event to see detailed information on what happened and the source of the information. The information shown in this map is based on the International Crisis Group CrisisWatch Database, the Global Terrorism Database and the ACLED Dataset.

Mali and surrounding countries show similar patterns of severe poverty that undermine development in the entire Sahel region, including neighboring countries Mauritania, Niger and Chad. The Sahelian people cope with their the economic uncertainty by working along informal and cross-border trade networks[2], keeping a nomadic population on the move in their search for food for their family and their cattle.[3] During periods of draught, scarcity often results in conflicts over land, water and food. In times of limited fertile land, too much stock can lead to overgrazing and desertification if the soil is not fully recovered. Development in agriculture, innovation and infrastructure can help mitigate food insecurities and strengthen the resilience of the population, and lay the foundation for economic recovery. This is the focus of the China’s support to Mali for example.

However, within such approaches social inequalities should be addressed within groups, Boukary Sangare, a Malian anthropologist, points out. Societal inequalities contribute to insecurity, including inequality in economic opportunities, development and representation which fuels conflict. Examples include the prioritization of men over women, of landowners over migrants and elder over the youth.[4] The Plan for the Sustainable Recovery of Mali of the Malian government addresses issues like gender inequality and reforming policies for equal socio-economic infrastructure.[5] But social inequalities cannot only be addressed through governance policies, there’s also a social aspect, which the French Development agency (AFD) addresses, including social cohesion, social mobility, openness and social dialogue.

slide_image

Not only access to formal economies should be addressed, also illicit forms. In nomadic societies, kinship and trade relations extend over countries creating an informal system as alternative to governance in the desert regions. In recent years, linkages have shifted considerably, as ethnic groups seek diverse, non-traditional sources of income to survive. In times of insecurity the population participates in the cigarette smuggle, human trafficking and drug trade in a very fluid way, according to Camino Kavanagh, advisor to Kofi Annan’s West-African Drug Commission.[1] Dependent on their ability to survive, additional means are sought.

Helpful is the EU’s Strategy for security and development in the Sahel, which analyzes socio-economic root causes of conflict in relation to the security the threats, stating that:

“allied terrorist and criminal groups in the Sahel represent immediate and longer-term risks to European interests because of their growing ability to take advantage of weak state presence and other prevailing conditions in the region, including ‘extreme poverty…frequent food crises, rapid population growth, fragile governance, corruption [and] unresolved internal tensions’.”[2]

The EU has also its focus on both the national as the regional level, one for the Sahel and two for Mali, a civil mission (EUCAP) and military training mission (EUTM). And a recent report of the EU’s Institute for Security Studies it is pointed out the a regional approach is necessary, while each of the countries have its own circumstances, to address the security threats that cross the borders.

Despite economic growth and development progress Africa remains doomed: three-quarters of the continent is portrayed as ‘critical’, and the other quarter as ‘in danger’ or ‘borderline’. This is what the Failed States Index 2013 claims.

In addition to its socio-economic challenges described above, Mali’s state performance appeared to be weaker than the role model country was perceived to be. The sudden collapse revealed this fragility, Martin van Vliet, researcher and advisor to the head of MINUSMA points out. The limited collective accountability role and poor legislative performance of Malian parliamentarians in the late 2000s, and the way in which the legislature failed to reflect the mounting frustration with the Touré regime, leading to a growing perception that the political class was out of touch. [3] According to him, the conflict in Mali is a socio-political problem. Therefore many international initiatives logically focus on strengthening the rule of law, which is for example central in the UN’s MUNISMA operation.

Powerrelations within the government are much harder address by external interveners. International development initiatives are mostly channelled through the central government institutions, spent by Bamako’s ruling elite,[4] which are fraud with activities and corruption, states Wolfram Lacher, researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and expert in drugtrade and corruption in West-Africa. He underlines the importance of networks that straddle the Sahara. Drug trafficking – together with smuggling in a wide variety of other goods – is a major source for enrichment in the Sahara. The area not only includes the Niger and Mali, but also Mauritania, Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and Chad. To succeed in this business, smugglers need logistics, a regional network, weapons, and political protection. At the same time, the profits generated from drugsmuggling have a profound impact on local socio-political structures, enabling traffickers to buy weapons, influence and social standing. This explains why drug smuggling in the Sahel-Sahara is so closely linked with both members of the political and business establishments (click the icon for more info), and leaders of armed groups – including extremist groups such as MUJAO. Such deep interstate criminal networks underline Lacher’s plea for a stronger external focus on political interests and processes. The drug market – from production to consumption – is conserved by political leaders in the Sahel region. The international political economy of drug trafficking should be analyzed on its harm and impact in West-Africa along the chain, shifts in policy in producer countries have proven to contribute to the relocation of trading routes in West-Africa, driven by European consumer countries and the United States. [LINK MABEL]

Lacher sums up a list of political figures who’ve been involved in drug trade in the Sahel region. A well-known corruption scandal is the ‘Air Cocaine’ incident.[1] In 2009 a Boeing 727 was found in the Gao desert carrying 10 tonnes of cocaine. Rebels were immediately accused, but without doubt corruption enabled the safe routing of the drugs passed security checks. And two years earlier in Mauritania, Sid’Ahmed Ould Taya, the former president’s nephew and Interpol liaison officer in Mauritania, was found to be involved in a cocaine transaction at the airport.[2] Sidi Mohamed Ould Haidallah, the son of another former president, was arrested and found guilty by a Moroccan court in relation with this case. In Niger, cases of narcotics and weapons smuggling have been linked to an advisor to the country’s former president, a prominent businessmen and senior figures in the ruling party, as well former Tuareg rebel leaders who are now in senior positions. During the first half of 2013, multiple sources in Niamey and Tripoli consistently suggested that a new smuggling network had been established in southern Libya by former leading figures in Niger Tuareg rebellions, a Gadhafi-era Libyan general and a businessman-cum-senator from a southern Algerian province.

Additionally, the powerrelations between the rebel groups politicians, and the hybridity of these relations, impact security analysis. Contrary to how the conflict has been framed in the media, it is not a fight of the Malian army against the Tuareg, but a fight of many conflicting ethnic and ideological groups. Conflict between and within groups over socio-economic, political, ideological and geographical factors creates a complex dynamic. Conflict analysis should integrate and create insights in this multiplicity.[1]

The MNLA, the group of Tuareg separatists, are in rebellion against their government. A second category of fighters are engaged in a violent jihad with ideological roots in Salafism, the

There’s a constant fluidity between the relationship between the different groups – Bambara, Malinké, Sorakole, Dogon and Songhay (farmers), Fulani, Maur and Tuareg (herders), Bozo (fishers) and the rebel groups MUJAO, AQIM, Ansar Dine, Ansar al-Sharia and the Arab Islamic Front of Azawad. And as mentioned before, these relationships build on extensive crossborder networks throughout the Sahel, which means that their influence and mobility stretches far. Local security interventions, like MINUSMA, can therefore set a so-called ‘waterbedeffect’ in motion. As extremist rebel groups cross African borders to seek refuge and to regroup, any local or national intervention will relocate the security problem to other regions, ready to return when the troops leave.

Particularly AQIM and MUJAO are notorious, who make profits from kidnapping Western nationals. The Canadian and numerous European governments paid ransoms that are estimated between $40m and $65m between 2008 and 2012 – possibly even more[1] and thereby enriching the groups. Also, most of the hostages were released in northern Mali, while being kidnapped in surrounding countries, which shows how easily they move.

More recently, in February 2013, two vans with Malian rebels are spotted in Darfur. In the days after Darfur rebel group Justice and Equity Movement (JEM) alleged that the Malian Islamist rebels were fleeing airstrikes on their positions and advances by ground forces from France, Mali, Chad and others and entered Sudan to seek refuge. They traveled from Mali via Libya, in full co-ordination with the Sudanese government and the North Darfur authorities[2]. The Sudanese army counters that they came via Sudan’s remote border with the Central African Republic. African governments providing shelter to rebels that adhere similar ideological and political interests further complicates peacebuilding interventions at a country level.

Negations between the countries involved in the region should give insight in the dynamics of the rebel groups and enable adequate responses. At the same time, the effect of external intervention on these dynamics. Other factors that come into play are the long-term trading relations with the country for which a stable and well-governed region is hoped. Mali is rich on gold, diamonds, petroleum and uranium, natural resources that are become increasingly scarce in the future, and that are ineffectively exploited in the Sahel. Currently many concerns exist over how these resources will be exploited. For example, many South-Malians accuse the French of colliding with the Tuareg to access the wealth of natural resources. Conflict and interventions are subjected to the interests of stakeholders and the analysis they make to strategically accomplish their goal.

Thus, there are a variety of aspects that should be taken into account when doing conflict analysis. Conflicting relations might be below the surface for decades, think of disputes over land, water, food etcetera, but pop up when there’s a direct occasion, which can then become the tipping point towards civil war. Strategies should include 1) a socio-economic focus on addressing the root causes of conflict, including food insecurity, inequalities and unemployment. 2) a governance focus on strengthening rule of law, end corruption and advance political representation. And 3) a security focus on immediate security threats, disarming violent groups and restoring stability. Currently, rule of law approaches have become the spearhead of most international involvement in the country. While this is crucial to advance governance, it is only partly helpful as they fail to address the socio-economic factors that destabilize the region. And in practice, the many analyses developed by the international community are reduced to security goals. MINUSMA’s mandate is set to support political processes and peacebuilding, but to the public the political debate is framed as a security intervention.

slide_video

For example, in a recent interview, the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, legitimized the participation of the Netherlands in the MINUSMA mission as a means to fight likeminded al-Qaeda rebels that want war with the West[1]. And in a recent meeting, initiated by several prominent Dutch knowledge institutes, where several attentends of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it was stated that in reality interventions are put in place so urgently, without taking time to do the necessary context analysis.

slide_video

Therefore, an understanding of the conflict in Mali requires an integration of the analysis of socio-economic, (socio-)political and security factors that undermine stability for the country and its population. However, what the strategies above in reality fail to do is to integrate the socio-economic destabilizing factors in the region. The analyses have been made extensively among multilateral institutes like the UN and the EU, and among knowledge institutes. For example, to the Norwegian Peacebuilding Research Center NOREF a socio-economic approach is their starting point.[1] And UNOCHA adopted socio-economic analyses on food insecurities, water scarcity and early warning systems.[2] Seeing insecurity at community level as one of the security threats, the European Delegacy in Bamako is trying to focus its approaches on community strategies, through community radio’s and community security provisions.[3] A consensus for a regional approach is growing, combining local and international perspectives for the entire Sahel region, but alongside this trend the limitations appear. For example the critique on inability to implementing such a strategy due to a lack of regional institutions that limit the EU’s impact.[4] Also regional cooperation between the stakeholders has proven to be difficult. For example after the AU/ECOWAS regional efforts lacked forceful action and the UN took over in the MINUSMA mission. Acknowledging the struggles in cooperation and transmission in regional peacekeeping operations, the UN Security Council in cooperation with the AU requested the UN Secretariat a lessons learnt exercise on the transitions from AU to UN peacekeeping operations in Mali (and the Central African Republic). By the end of 2014, clear recommendations for future transitional arrangements can provide a step forward in regional cooperation for personnel and facilities.

slide_author

Furthermore, along with an integration of these factors, a clear geographic scope is required. As countries should advance their cooperation on insecurity and instability, a clear scope and end-goal determines the approach. Some include all countries from west to east to Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia to define the Sahel from a socio-economic perspective. Others opt for a Sahara-Sahel governance approach from Algeria to Niger, addressing the fragile states in the region that are unable to govern their countries properly. Or security analyses compare conflicts from West Africa with the uprisings in the MENA region, Syria and Iraq, presenting it as a girdle of safety threats that are not addressed by the country’s weak governments.[6] Some even include Ukraine in the girdle. Such different analysis can be helpful and additional to each other, however currently they’re used as parallel processes.

Ivan Briscoe, Clingendael

Mabel Gonzalez

Sahs Jesperson

Bruce Whitehouse

Sue